Struggling with Assurance? Or Is It Religious OCD?

Many Christians understand questions of assurance as a theological problem, whereas they are, in many cases, psychological in nature: “religious OCD” or "scrupulosity."

In my years of counseling, I have been struck by how many people have come to me with serious anxiety about their salvation. It is often framed as “struggling with assurance” or “dealing with a constant need to repent.” These counselees describe the need to continually repent all day long for minor things like “taking the Lord’s name in vain” when they use God’s name in an ordinary way. Or they are just plagued with doubts of whether they are actually saved, and they dwell on this question instead of enjoying their salvation.

These cases range from mild doubts that get in the way of communion with God to full-blown panic attacks that require medical care and everything in between.

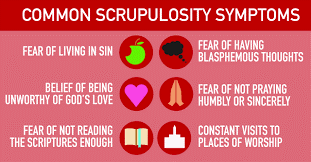

The problem is that many Christians understand questions of assurance as theological in nature, whereas they are, in many cases, primarily psychological: “religious OCD” or "scrupulosity."The stereotype of OCD is someone who needs to wash their hands all the time or keep things exactly in the right order. By comparison, people with religious OCD need to wash themselves clean continually of sin, psychologically or ritually, and to keep their spiritual life in exact order.

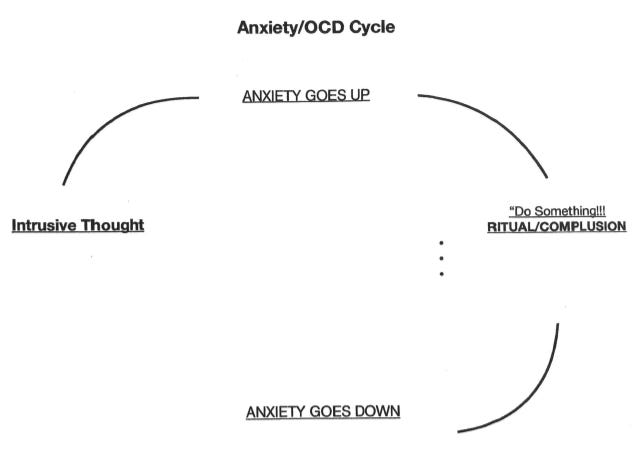

You might think that someone who is struggling with assurance of salvation just needs to memorize Romans 8 and pray more. They need to dwell on the promises of God every hour of the day. However, this focus on doubts and assurance is actually like telling someone with OCD to wash their hands more and focus on setting things straight more. It exacerbates the issue and makes the OCD worse.

The DSM defines obsessions as"persistent ideas, thoughts, impulses, or images that are experienced as intrusive and inappropriate that cause marked anxiety or distress." A lot of people call them “sticky thoughts” that you can’t get rid of and they plague you like swarming flies that won’t leave you alone.

The DSM says compulsions are “repetitive behaviors or mental acts, the goal of which is to prevent or reduce anxiety or distress.” In the case of religious OCD, the repetitive mental acts actually become repenting or focusing on the promises that have the goal of quieting the obsessive scary thought. Thus, if you just focus on assurance, you are helping them keep their cycle of obsession-compulsion.

The main way to help someone with religious OCD starts by just explaining what is going on physically. While it of course is still a spiritual issue, our bodies are fallen and affected by various miseries and disorders. Mike Emlet, a counselor at the Christian Counseling and Education Foundation (CCEF), says that sometimes when these thoughts come, they are not sinful in themselves but “bodily provocations.” He says, while “the somatic aspect of our constitution (body/brain) is ultimately not the ‘cause’ of sin, we must never underestimate the overwhelming tyranny of the bombarding thoughts these sufferers can face.”

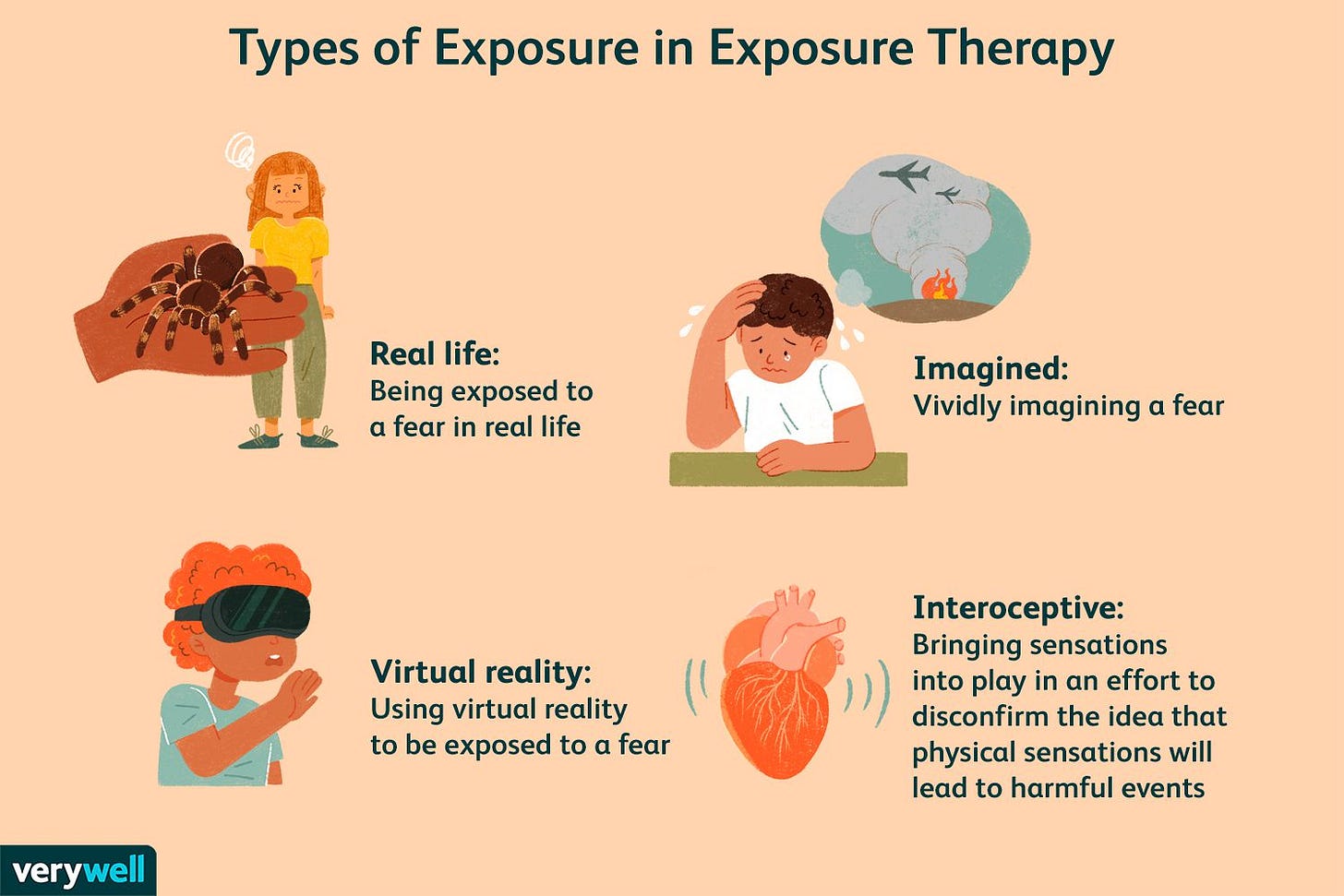

Once the sufferer understands that the body is provoking them and that it is not primarily a theological issue to continually investigate, the alarm bells will decrease. When the fear or contamination decreases, the obsessions and compulsions begin to subside. Further help can be found in “exposure-response prevention” (ERP), which is the main way to treat OCD. You are gradually exposed to your fear (like dirtiness or blaspheming God) which causes the brain to understand that there is no danger there and you don’t need to practice the compulsion (washing away the dirt or going through your ritual of repentance). Medication is often extremely helpful and necessary to calm the alarm bells and give a path to healing as well.

There are of course many spiritual issues you can explore with OCD sufferers like the need to control, black-and-white thinking, or trusting God, but if you miss the brain-body issue at the root, you might be excacerbating the problem. If you compulsively obsess about assurance or sin, the alarm bells will get louder and more overwhelming. Interestingly, those who struggle with religious OCD don’t always suffer from any kind of physical OCD like being overly concerned with cleanliness, so it often goes undetected.

However, religious OCD has been documented throughout Christian history, being called “scrupulosity” or “the doubting disease.” Prominent Christians who may have suffered from it include Martin Luther, St. Ignatius of Loyola, and John Bunyan. These theologians had “hijacked consciences” that plagued them and caused real suffering, but God used them for his purposes. This diagnosis does not undermine the value, for example, of Luther’s contribution to the doctrine of justification by faith alone. If not for that truth, maybe we would be right to experience religious OCD and scrupulosity!

While understanding and believing the gospel is fundamental to salvation, a particular person’s difficulty with assurance may not best be solved by “believing the gospel” anew. We should recognize the fallenness of our minds. Sometimes, psychology is able to describe well and intervene even in problems that seem religious in nature. Religious OCD or scrupulosity is one of those areas. This can help us understand and help other Christians better when they struggle with assurance.

Recommended Resources:

Mike Emlet’s article and talk on religious OCD at CCEF is one of the best introductions to this diagnosis.

A good introduction to OCD in general is Overcoming Obsessive Thoughts: How to Gain Control of Your OCD by David A. Clark and Christine Purdon. There is a chapter in there specifically on religious OCD as well.

To read more about it in church history, Can Christianity Cure Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?: A Psychiatrist Explores the Role of Faith in Treatment details many Christians’ experiences of it in church history.

The Doubting Disease: Help for Scrupulosity and Religious Compulsions by Joseph W. Ciarrocci is another good introduction with a historical perspective.

Thanks for the article. There are many Christians who have little expertise or know about the OCD condition.

Has there been a type of compulsion that result in massive amounts of time spent in research over moral issues? Like a person has a scrupulous thought or an inner moral debate and spend literal hours (even odd times at night or work) to continue "researching" the question by googling, reading, etc.